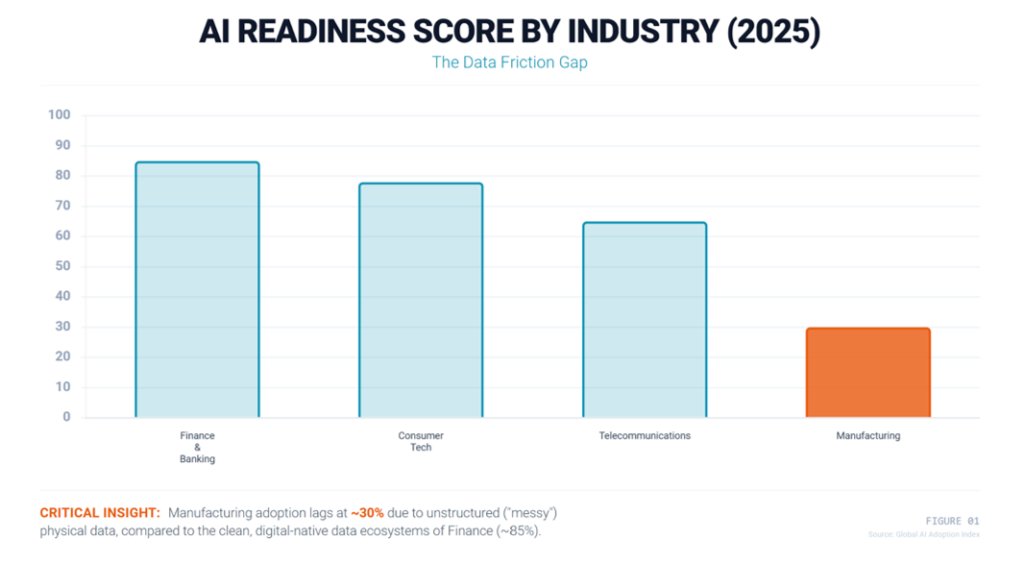

Manufacturing is arguably the sector with the greatest potential for AI empowerment. The promise of predictive maintenance, quality control, and process optimization is theoretically immense. However, a paradox defines the current industrial landscape: while factories generate more data than arguably any other sector, they have progressed far slower in AI adoption than finance, the Internet, or consumer goods.

Why is it so hard for factories that need intelligence the most to use it? The answer is not that people don’t want to succeed, but that there are three structural frictions where the logic of algorithms doesn’t match up with the logic of the actual world.

- The Data Friction: Standardized AI vs. The “Messy” Floor

Artificial intelligence works best in sterile, digital-native spaces where data is tidy and well-organized. But the factory floor is a place with “high entropy.”

In factories, data is often stuck in old silos or formatted in ways that don’t match. Consider quality control: for an AI to detect a defect, it needs thousands of standardized images of that defect. Yet, in many factories, defect data is incomplete or relies on human notes that lack digital annotation. A notable example from the BRICS Smart Manufacturing Case Series highlights a Chinese firm’s struggle with “quality data lifecycle management.” [1]The firm succeeded only by overhauling its entire data infrastructure before deploying a single model.

This illustrates a severe resource asymmetry: large enterprises can afford to “clean” their physical reality to make it machine-readable; SMEs cannot.

- The Operational Friction: Iteration vs. Stability

There is a fundamental clash of cultures. The ethos of AI development is “move fast and break things”—rapid iteration and experimentation. The ethos of manufacturing is continuity, stability, and safety.

A factory manager’s primary directive is to avoid downtime. Running an experimental algorithm on a live production line is an unacceptable risk. We see this tension at Siemens’ electronics facility in Erlangen, Germany. There, the company utilizes “digital twin” [2]technology to simulate operations in a virtual environment before touching the physical line. This works, but it makes it hard for new businesses to get in: only enterprises with enough money to develop a virtual factory may safely improve their real plant. For the others, the risk of interrupting steady output is greater than the possible benefits of intelligence.

- The Knowledge Friction: Master Craftsmen vs. Data Scientists

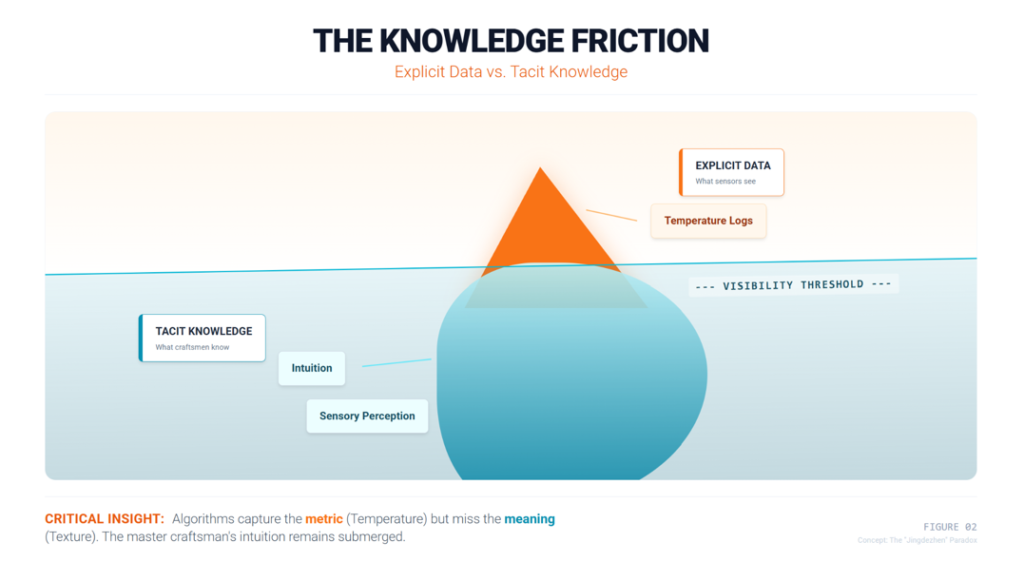

The knowledge gap between those who write code and people who know how to do it may be the biggest problem.

The digital transformation of Jingdezhen’s ceramics sector is a good example. Sensors and motion capture can record the temperatures of kilns and the ways that people throw, but they have a hard time capturing the “tacit knowledge” of a great craftsman. Critical assessments in clay preparation or glazing frequently rely on sensory perception—a tactile awareness of the material—that defies binary classification.

Data scientists often write down the metric (temperature) but forget to write down the meaning (texture). This suggests that the future of industrial AI isn’t about taking over jobs; it’s about “human-machine co-interpretation.”

The Real-Life Example: China’s Plan for Integration

Because of these tensions, China’s recent route shows how to avoid these challenges by employing scale.

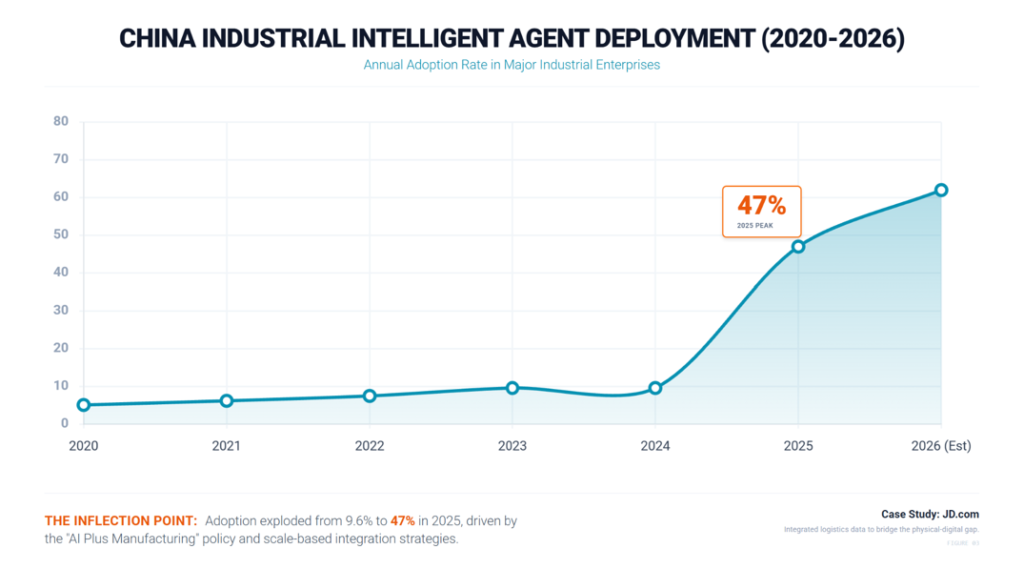

The data from 2025 is interesting since it reveals that the added value of industrial enterprises grew by 5.9%. The utilization of huge language models and smart agents went grown from 9.6% in 2024 to 47.5% in 2025, which is even more impressive. This big jump signifies that the “adoption threshold” has been passed.

This was not accidental. The “AI Plus Manufacturing” plan, released in January 2026, focuses explicitly on the “seven key tasks” required to standardize the industrial data layer.

We see the practical application of this in JD.com. [3]Rather than treating AI as a standalone tool, JD.com utilized its massive accumulation of logistics data to train JoyIndustrial, a large-scale industrial supply chain model. This approach works because it solves the “Data Friction” mentioned earlier: by integrating supply chain insights with factory floor data, they created a context-rich environment where the AI could actually function. It proves that deep integration with the physical industry is the only way to make the digital intelligence work.

Conclusion: The BRICS Imperative

The global economy is undergoing a profound transformation. However, if the “cleaning” of data and the building of “digital twins” remains expensive, the Global South risks falling into a “compute divide.”

This is where the BRICS mechanism is essential. Developing nations—from Brazil to South Africa—cannot fight these frictions alone. We need an “imported capability” strategy similar to the UAE’s, but facilitated through the BRICS AI Development and Cooperation Centre.

By pooling our resources—China’s manufacturing datasets, India’s software capabilities, and Russia’s mathematical expertise—we can lower the cost of entry. We can share the “pre-trained” industrial models (like JoyIndustrial) so that every nation does not have to reinvent the wheel. Only through such cooperation can we ensure that the factories of the Global South become intelligent, rather than obsolete.

[1] https://www.szsandstone.com/company-dynamics/616?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[2] Siemens unveils technologies to accelerate the industrial AI revolution at CES, 2026

[3] https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1853922230357248919&wfr=spider&for=pc

No comment yet, add your voice below!